Lessons from the Jungle: Living, Working, and Growing together.

Nicole Shen, Kirill Donov, and Olivia Ghiaur

June 30, 2025

Hello world! We are a team of three McGill engineering students going into our third year. Our disciplines range from bioengineering to chemical engineering, giving us a wide range of theoretical knowledge on everything plants, soil, and chemicals. Through our shared love of the environment and desire to explore, we found Siendo Naturaleza.

The project we are currently working on with Siendo Naturaleza revolves around regenerating an ancient indigenous practice of creating terra preta de indio, incredibly rich, anthropogenic, agricultural soils initially found in the heart of the Amazon rainforest. Terra Preta (known by the Kichwa Lamistas as Yana Allpa) was developed through careful observation and long before knowledge of the effects of elemental proportions on plant and crop yield.

While working on this project, we live at Sacha Isla, which embodies a sustainable lifestyle for group living. The team consists of the three of us, three other interns working on a micro hydroelectric project, Eliane and George (the Directors of the program), and the Siendo Naturaleza team. Moving away from North America and spending over two months in Peru, we have become family, albeit forced.

Our past experiences and expectations did not perfectly translate into living and working on the land but our time here is shaped by unexpected circumstances.

Living

Lessons from the jungle

The message board in our main shared space, the Amigrillo, reads “Keep in mind ‘jungle hygiene.’ More mindful, cleaner, tighter.”

From the silicone spatulas that get fully wrapped up or put away immediately after use to prevent being preyed upon, to the rat’s nest that took a liking to one of our peers favorite sweatshirts that was left out. Living in the jungle requires immense thoughtfulness. A mistightened jar of honey will be taken over in mere minutes by hundreds of ants and a wooden spatula put away too early will invite mold overnight. Trial and error of jungle life takes time, and we will continue to learn lessons through our own unique experiences.

Working in your living space and living in your working space

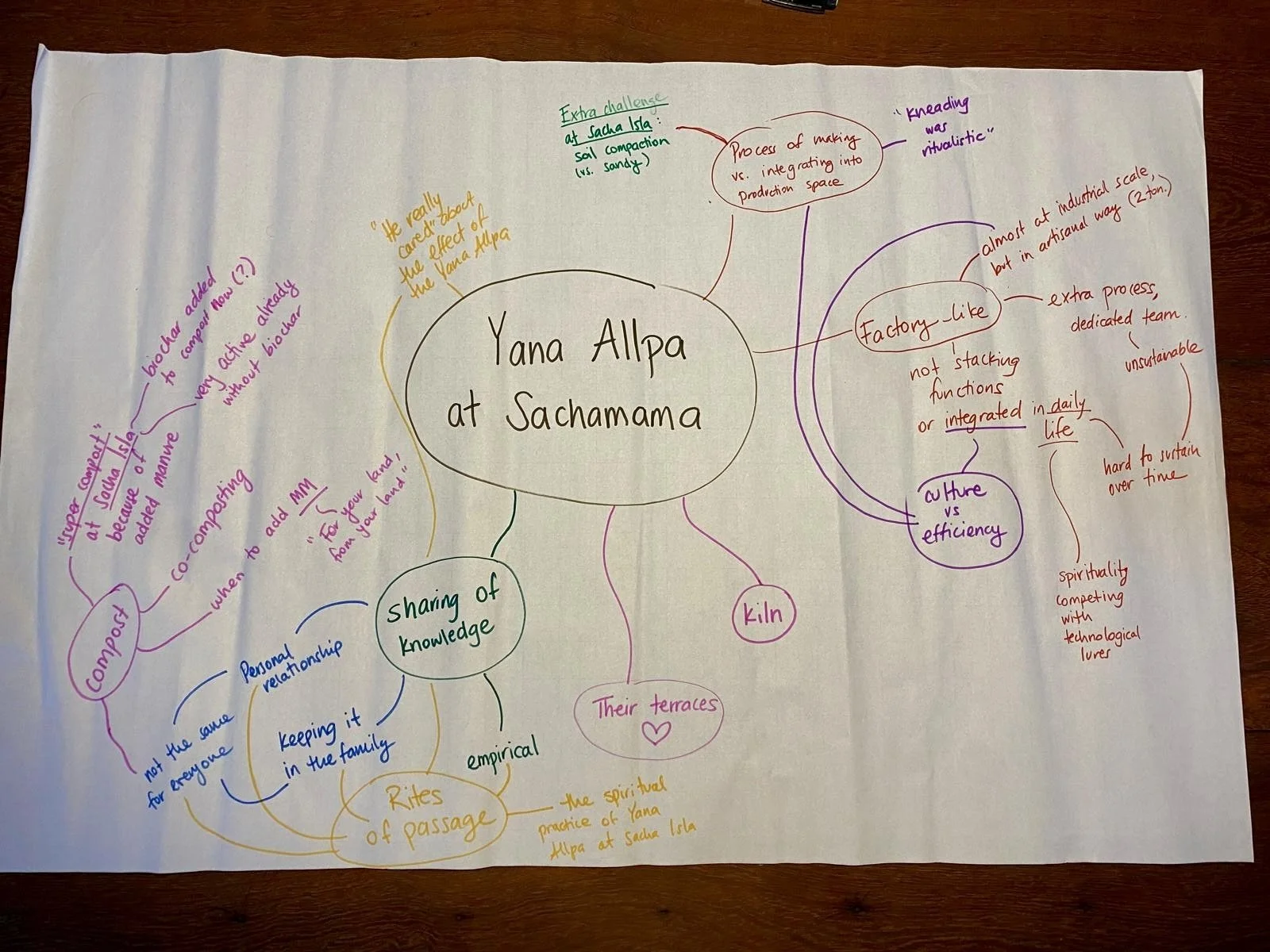

The space of the Amigrillo, a two platformed, open-concept area with a table on the first floor and scattered with hammocks throughout, serves as both our primary work-space on sessions where we engage in planning and research and our main community area. It’s where we’ve learned to play games, like Hive, a two-player strategy based game which revolves around capturing a queen bee, but also mind-mapped our experience at the Sachamama Center for Biocultural Regeneration in Lamas.

This idea of working in your living space and living in your working space wasn't completely a foreign concept to us, having gone through COVID. However, the addition of living with the people we are working with creates tension, builds community, and fosters creativity all at the same time. This togetherness among the whole team, while at times overwhelming, allows us to better understand each other and opens the space to a cross pollination of ideas.

Community living

What does it mean to live in a community? It’s not feeling pressured to wash everyone’s dish, being mindful of your portion size when you’re first in line to eat, or being an extra helping hand to clean when you have the energy. We have learned that it is about letting people love you and accepting that love. Even though it may be hard to do at times, it is something we are working towards.

Our daily morning rotas, or chores, also help us realize this. They span various tasks that bring us closer to being able to fully sustain life on the land. We manage waste and feed the soils through the creation of compost and humanure. We plant seeds and help clear trails or invasive grasses. We help harvest fruits in the kitchen for the day ahead and prepare meals with what’s available.

Our responsibility being here is not only to ourselves. We have a responsibility to each other, our project, the land, and the greater community of the Tiracu Valley. Through connecting with the greater community through the holiday of San Juan, unique to the Peruvian Amazon, playing with the kids, and experiencing a Father’s Day party, we have begun to fully understand the culture of the area, bringing unique insights to our work. On the land, we have learned to live sustainably with the Earth, feeding our connection to the soil which provides our sustenance. Within our project, we have learned to rely on other’s strengths to cover our weaknesses and within our community of interns we have been taught the value of communication and support.

Ultimately, each community that we have been accepted into has given us its own unique lessons.

Working

When it comes to working at Sacha Isla, many theoretical factors did not quite translate into the real world. Some are perspectives that we should have considered, others things could only have been learned by doing.

Workplan

When developing a work plan before arriving at the land, our team was expecting an immediate start, easily launching into the project with only our background knowledge as context and then maintaining a steady stream of output over the nine week period. Instead, we took nearly a week to become acquainted with the workspace, tools, necessary materials, and each other. Even now, writing two weeks after arriving at Sacha Isla, we are not completely familiar with the land boundaries, materials in the materials bank, or used the knowledge of the team to our full advantage.

We also quickly realized that there was simply no way to make use of every minute of the work time. Unlike working online, it takes physical time and energy to get from one place to the next, perform physical labor, and develop our theories. Compost takes time to decompose, mycelium takes time to grow, sugars take time to ferment, and people take time to recharge. In order to be realistic with our time, we have had to plan the space in our schedules to allow time to take it’s course.

Other than the system of working on the land, our team had to undergo some mental reconstruction in the context of the project. The constraints which we had identified before arriving to the land were no longer the highest priority and instead new ones emerged. For example, working in a low/no-waste framework was something that we had anticipated as a major challenge. Instead, this system is so well integrated into the way of life on the land that it has not yet barred us from any goal. However, the cultural perspective, which we had expected to adopt from our research, has required much more mindfulness, energy, and consideration than previously anticipated. Over the upcoming weeks we are preparing to develop our own knowledge base regarding the integration of culture on the land, through interviewing and shadowing the people who regularly live with the land.

Finally, as students of theory, the goal is always both quality and quantity. In class projects, it can be assumed that you will have all of the resources, personnel/labor, and intelligence necessary to complete any lofty goals. In real life, the scale of the land, and thus the project, is far more limited by our abilities and time. Living in Sacha Isla for only nine weeks, with a full week dedicated to learning the land, does not allow for the time to watch compost fully decompose, evaluate a plant’s full growth cycle, or expand the project to its fullest extent. Even though that is not what we had hoped, the opportunity to engage with Yana Allpa at this time scale invites purpose and intention in each component every day.

Concepts in Action

The learning centre is deeply invested in the practice of human-centered design (HCD). As a design philosophy, HCD focuses on the holistic. Beyond efficiency and aesthetics, it considers the needs and experience of the user. At Siendo Naturaleza, we were in awe of the thoughtfulness that went into every little detail. In the design process, this attention to detail begins with observation of the land, its inhabitants, and the interactions between.

One noteworthy example is the kitchen. It is carefully situated in between the dining area and the Amigrillo. One thing that stood out to us is the experience of washing dishes. The washing/drying area is located at the back of the kitchen, and is an open-sided area, inviting you to witness the jungle while you wash the dishes. The sponges used for washing are naturally grown loofahs, which are just as good at removing residues and are enjoyable to handle. These loofahs have a neat mesh drying area. The dish drying area consists of evenly spaced bamboo stalks, allowing water to drip through. As a whole, the experience of using the kitchen is very captivating. It's not just about getting the job done, it's about immersing the senses and leaving the area feeling revitalised.

Unlike the kitchen, our accommodations are still in the observation stage of the design process. Although the main construction was completed, elements such as furnishing, lighting, and decor were still in development. We were lucky to be the users who were interviewed on our experience. In particular, George surveyed us on the lighting system. I was surprised by the power of experiencing a place in facilitating its development. Details which would otherwise have been ignored have been brought to light by living in the space. Being the direct users of the design, we gained a greater appreciation for HCD because we saw how our needs were directly considered. Another aspect that we discovered was that HCD is a cycle, and not a linear process. It is a repeated iteration of observation, implementation, and consultation. This is what separates HCD from conventional practices, it is an approach that constantly strives to improve the experience of its users.

These experiences helped us develop an understanding of HCD which we later implemented in our own work. In particular, we considered how to implement a system of crushing biochar, a key ingredient in Yana Allpa. After testing a range of different prototypes, we found that walking over woven bags filled with biochar yielded the best grind size relative to effort. The main challenge was to find a way to integrate this practice into daily life here. As usual, we began with observation. We decided it would be best to place the bags in a commonly walked area. We had to consider where it would fit the most, and be convenient to implement. We are still in the process of prototyping and excited to see where this takes us. Overall, it was insightful to experience HCD both from the side of the user and the designer.

Conclusion

The jungle dictates our work schedule and what you can do in leisure time. It wakes you up when it wants to and guides what we eat for our meals. It invites you to listen and observe closely, a concept that we were disconnected from in the busy cities we live in. Every observation shapes the development of our project, and we are excited to learn not only about Yana Allpa, but about ourselves, and each other.

Nicole Shen, Kirill Donov, and Olivia Ghiaur

Interns, Regeneration Challenges Internship

Undergraduate engineering students at McGill University